At Fault is Kate Chopin’s early novel about a young widow seeking to reconcile her own needs with those of the people she is responsible for.

Painting by Joseph Rusling Meeker, “Bayou Teche, Louisiana,” 1883. Courtesy St. Louis Art Museum

By the Editors of KateChopin.org

Reading At Fault online and in print

Characters

Time and place

Themes

When the novel was written and published

Questions and answers

New: A 2022 book of critical essays about the novel

At Fault in a Brazilian translation

Accurate printed texts

Articles and book chapters about the novel

Books that discuss the novel

Reading Kate Chopin’s At Fault online and in print

The novel is now available online at the Project Gutenberg site. You can download it or you can read it online. It’s searchable by word or phrase or chapter number, and it’s an accurate, trustworthy text.

In print you can find a copy in The Complete Works of Kate Chopin, in the Penguin Classics edition of At Fault, in At Fault: A Scholarly Edition with Background Readings, and in the the Library of America Kate Chopin volume, as well as in other paperback and hardcover editions. You’ll find publication information about these books below.

At Fault characters

Place-du-Bois characters:

- Thérèse Lafirme: owner of the Place-du-Bois plantation

- Uncle Hiram: employee of Thérèse

- Aunt Belindy: cook for Thérèse

- Betsy: household employee of Thérèse

- Mandy: household employee of Thérèse

- Grégoire Santien: nephew of Thérèse; his brothers Hector and Placide appear in Chopin stories “In Sabine,” “A No-Account Creole,” “In and Out of Old Natchitoches,” and “Ma’me Pélagie”

- David Hosmer: manager of the sawmill on the Place-du-Bois plantation

- Melicent Hosmer: sister of David

- Joçint: employee of Hosmer at the sawmill

- Morico: father of Joçint

- Aunt Cynthy, Suze, Mose, Minervy, Araminty: employees and relatives of employees at Place-du-Bois

- Sampson: employee of Thérèse assigned to work at Fanny’s home

- Marie Louise: [called “Grosse tante” in French, “Big Aunt”] Thérèse’s childhood nurse and attendant

- Pierson: employee of Thérèse

- Joseph Duplan: owner of Les Chênières plantation; he appears also in Chopin short stories “A Rude Awakening,” “After the Winter,” “A No-Account Creole,” and “Ozème’s Holiday”

- Mrs. Duplan: wife of Joseph; she appears in “A No-Account Creole” and “A Rude Awakening”

- Ninette Duplan: daughter of Joseph and Mrs. Duplan; she appears in “A No-Account Creole”

- Rufe Jimson from Cornstalk, Texas

- Johannah: household servant of Melicent Hosmer

- Nathan: employee who manages the ferry on the Cane River

- Aunt Agnes: employee on the plantation

- a teamster crossing the Cane River

St. Louis characters:

- Fanny Larimore Hosmer

- Belle Worthington: friend of Fanny

- Lorenzo Worthington: husband of Belle

- Lucilla Worthington: daughter of Belle and Lorenzo

- Lou Dawson: another friend of Fanny

- Jack Dawson: husband of Lou

At Fault time and place

At Fault is set in the late nineteenth century in Louisiana and St. Louis, Missouri. Except for the few chapters in St. Louis, the novel plays out on the Place-du-Bois plantation on the Cane River in northwestern Louisiana, near Natchitoches, not far from the Texas border. As in Kate Chopin’s short stories, the characters in the novel, like many of the people living in Louisiana at the time, are Creoles, Acadians, “Americans” (as the Creoles and Acadians call outsiders), African-Americans, Native Americans, and people of mixed race. Except for Thérèse Lafirme, David Hosmer, and their families, most of the Louisiana characters are poor, because the area has yet to recover from the devastation of the Civil War. Many of the Louisiana characters speak French and Creole as well as English, so the novel contains phrases in French and Creole.

At Fault themes

Many readers and scholars think of At Fault as a divorce novel, one of the first novels in the United States to focus on the ethics of divorce. Other people explore the book’s emphasis on economic and technical restructuring in the American South after the Civil War, on racial undercurrents in the book, or on the subjects of alcoholism or violence. Some readers find elements of sentimentality in the novel, while others find solace in its hopefulness and its celebration of married love. You may want to look at the questions and answers below. And you can read about finding themes in Kate Chopin’s stories and novels on the Themes page of this site.

When Kate Chopin’s At Fault was written and published

The novel was composed between July 5, 1889, and April 20, 1890. Chopin sent the manuscript to Belford’s Monthly, a magazine in Chicago that published a novel in each issue, but after the editor turned it down, she had a thousand copies printed privately by the Nixon-Jones Printing Company in St. Louis in September 1890. She sent copies of the book to newspapers in several cities, but the critics were not impressed with the work, and their reviews were in general tepid.

You can find complete composition dates and publication dates for Chopin’s works on pages 1003 to 1032 of The Complete Works of Kate Chopin, edited by Per Seyersted (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969, 2006).

Questions and answers about At Fault

Q: I love The Awakening, but I don’t know At Fault. Should I read it? Is it any good?

A: Yes and yes, but with qualifications. If you fell in love with The Awakening at some point in your life and want to preserve that magic moment by remembering Kate Chopin as you knew her from Edna Pontellier’s story or from Chopin short stories like “The Storm,” “A Pair of Silk Stockings,” “The Story of an Hour,” or a few others, then perhaps you should read no further. If, though, you want to know Kate Chopin more fully, as a woman not only way ahead of the times but as a complex, sophisticated woman of the times, then reading some of her other stories and her early novel is a good idea.

As early as 1970, some critics were writing about the value of the book. At Fault, Lewis Leary writes, is “a story of love and the possibilities of freedom. It speaks of love that restricts and of love that is genuine, of freedom that harms and of freedom that is livening. It suggests questions about the rights of love when convention intervenes.”

And “jsgoldn” in a recent internet review writes, “If you’ve read The Awakening and could appreciate the ideas and writing, but were not as impressed with it as others tend to be, try At Fault. It’s compact story that I wish were developed further because of its originality and intrigue. Don’t take Kate Chopin off your list after The Awakening—try this one!”

Q: Why are there so many French expressions in the novel? If I don’t read French, how do I know what those expressions mean?

A: Most of the characters in the book—like those in Kate Chopin’s short stories and The Awakening—speak French, Spanish, Creole, or all three, in addition to English. Many people with French and Spanish roots live in Louisiana, and some of them speak more than one language. Like Mark Twain and other writers of her time, Chopin was determined to be accurate in the way she recorded the speech of the people she focused on in her work. Some editions of At Fault (like the Penguin edition and At Fault: A Scholarly Edition with Background Readings) include translations of French expressions, and Chopin usually subtly glosses such expressions in the text. Missing the meaning of a French expression is not likely to lead to a mistake in understanding the novel.

Q: I don’t understand. Why does Joçint burn down the sawmill?

A: Joçint, half Native-American, half African-American, loves the freedom of hunting in the forest. But Morico, his father, forces him to work at the sawmill instead, a job he hates. In fury, he burns down the mill. There are implications in the novel that Joçint resents the presence of a white, industrial business man from the North (St. Louis) who is cutting down the trees in his beloved forest.

Q: I’m not a native speaker of English and I struggle with the dialect in some passages of this novel. How and why, exactly, does Grégoire die? Are the reasons implied in the story? The conversation between Thérèse and Rufe Jimson contains dialect too heavy for me to understand.

A: Grégoire is deeply in love with Hosmer’s sister, Melicent, but she rejects him. In despair, he goes to Texas, where he picks a fight with an armed man and is shot.

The novel says:

“You see it all riz out o’ a little altercation ’twixt him and Colonel Klayton in the colonel’s store. Some says he’d ben drinkin’; others denies it.”

[You see (understand), it all rose out of a little altercation (argument) between him (Grégoire) and Colonel Klayton in the colonel’s store. Some (people) say he (Grégoire) had been drinking (alcohol of some sort) but others deny it.]

“He’s dead?” gasped Thérèse, looking at the dispassionate Texan with horrified eyes.

“Wall, yes,” . . . It’s true ’nough, the young feller hed drawed, but thet’s no reason to persume it was his intention to use his gun.”

[Well, yes. . . . It’s true enough that the young fellow (Grégoire) had drawn (taken out his gun) but that’s no reason to presume (suppose) it was his intention to use (it).]

Q: Also, I couldn’t understand this sentence in Fanny’s speech about how Hosmer treats his newspaper–especially, the word, “figuring” in this context:

“I [Fanny] believe it’s the only thing he [Hosmer] ever thought or dream about; that eternal figuring on every bit of paper he could lay hold of, till I was tired picking them up all over the house”

A: “Figuring” in this context means calculating numbers of some sort. Apparently, Fanny thinks that Hosmer, who is a good businessman, spends too much of his time calculating business expenses or business profits on pieces of paper, which he leaves all over the house. Hosmer must be studying newspaper reports of the stock market or of commodity prices and then calculating how those numbers affect his business. Fanny is upset because he is not paying attention to her and her needs.

Q: How would you classify this book? Is it realism or romanticism or naturalism? Is it a sentimental novel, a local-color novel, a thesis novel?

A: Critics have called it all of those and various combinations of them. Donna Campbell in the recent Cambridge Companion to Kate Chopin writes that At Fault “represents Chopin’s only sustained, fully developed attempt as writing in the influential nineteenth-century genre of the social-problem novel.”

Such books, Campbell writes, describe “works that dramatised complex social ills and tried to influence public debates over such issues as treatment of the poor, industrial conditions, and labour-management disputes. As a genre, they often incorporated the very features that twentieth-century critics have found so problematic: multiple subplots, a profusion of themes, and numerous characters, some seemingly extraneous, that may not advance the protagonist’s moral growth but instead serve to illustrate a particular social ill.”

And Bernard Koloski in the introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of At Fault, says it is “Kate Chopin’s novel of hope.” Its “story of second chances,” he writes, “of starting over, of salvaging wrecked lives, contains a troubled picture of nineteenth-century America’s ambivalence about failed marriages and economic restructuring. The novel raises questions that have no easy answers. But like most of Chopin’s best work, it is optimistic. Amid uncertainty and pain, amid violence and destruction, it celebrates the redemptive power of love.”

Q: I am new to the wonderful fiction of Kate Chopin. I finished The Awakening in record time and have begun At Fault. I have a question I am hoping that you might help me with. The novel has a publication date of 1890. However, I have just come to Chapter 9 in Part I of the novel when Hosmer has traveled to St. Louis, and there he encounters hundreds of visitors who have come to St. Louis for the Exposition. Didn’t the St. Louis Exposition take place in 1904, fourteen years after the publication of the novel?

A: The St. Louis Exposition was not the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, known as the St. Louis World’s Fair, the 1904 fair celebrated in the 1944 American musical film “Meet Me in St. Louis.”

The St. Louis Exposition was held for forty days each year starting in 1884. It took place at a building on Olive and Thirteenth streets, a site now occupied by the main branch of the St. Louis Public Library. It included areas for music, the arts, the sciences, manufactured goods, and farm products.

That and other details are explained in the notes to the Penguin Classics edition of At Fault.

You can read more questions and answers about Kate Chopin and her work, and you can contact us your questions.

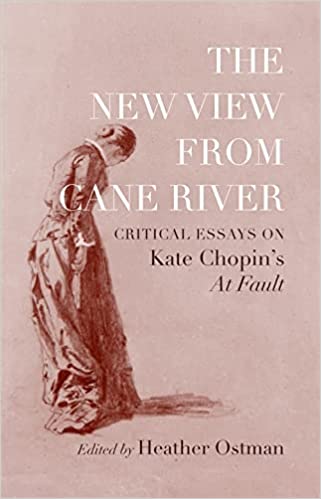

A New Book of Essays about Kate Chopin’s Early Novel

The Louisiana State University Press published The New View from Cane River: Critical Essays on Kate Chopin’s At Fault on July 6, 2022. The Press writes, “The book features ten in-depth essays that provide fresh, diverse perspectives on Kate Chopin’s first novel, At Fault. While much critical work on the author prioritizes her famous, groundbreaking second book, The Awakening, its 1890 predecessor remains a fascinating text that presents a complicated moral universe, including a plot that involves divorce, alcoholism, and murder set in the aftermath of the Civil War.

“Edited by Chopin scholar Heather Ostman, the essays in The New View from Cane River provide multiple approaches for understanding this complex work, with particular attention to the dynamics of the post-Reconstruction era and its effects on race, gender, and economics in Louisiana. Original perspectives introduced by the contributors include discussions of Chopin’s treatment of privilege, sexology, and Unitarianism, as well as what At Fault reveals about the early stages of literary modernism and the reading audiences of late nineteenth-century America.

“This overdue reconsideration of an overlooked novel gives enthusiastic readers, students, and instructors an opportunity for new encounters with a cherished American author.”

In addition to Heather Ostman’s Introduction, the book contains these essays:

Williams, Deborah Lindsay. “Absent Babies and Cosmopolitan Bananas: Fault Lines, Networks, and Modernity in At Fault”: 13-31.

Aikens, Natalie. “Reconciling the (Post)Plantation in At Fault: Reunion Romance, Western Expansionism, and the (Neo)Liberal Turn”: 32-63.

Knight, Nadine M. “At Fault and Antebellum Nostalgia”: 64-83.

Toth, Emily. “So Melicent Is a Unitarian: Who’s at Fault?”: 84-96.

Koloski, Bernard. “What Hosmer Wants: Male Aspirations in At Fault”: 97-114.

Bibler, Michael P. “Kate Chopin’s Queer Etiologies: What’s at Fault in the History of Sexuality”: 115-134.

Staunton, John A. “Quick, Dead, and Widowed: Failed Reading of ‘Unwholesome Intellectual Sweets’ and the Importance of Knowing Whose Story You’re In”: 135-155.

Ostman, Heather. “Divorce and the New Woman: Precedents to Modernism in At Fault”: 156-174.

Moldow, Susan. “Personified Matter: Empowered Things in At Fault.” 175-195.

Gil, Eulalia Piñero. “‘Thérèse Was Love’s Prophet’: The Emotional Discourse and the Depiction of Feelings in At Fault”: 196-214.

Aparecido D. Rossi (São Paulo State University, Brazil, and the University of California at Riverside) has sent us information about Carmem Lúcia Foltran’s 2005 translation of Chopin’s At Fault (ISBN: 85-992-7902-5). Carmem Foltran is an academic Brazilian translator of literature in English. She is also responsible for the second translation of The Awakening into Brazilian Portuguese, published in 2002.

Editora Horizonte is a Brazilian publishing house founded in 2005 by Eliane Alves de Oliveira. The translation of At Fault is its second published book (the first one was Cosima, by Nobel Prize winner Grazia Deledda). The cover, Aparecido Rossia tells us, is “a black and white composition designed by Renato Mendonça using the well-known picture of Kate Chopin and her first four children.”

For students and scholars

Accurate printed texts of At Fault

The Complete Works of Kate Chopin. Edited by Per Seyersted. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969, 2006.

At Fault. Edited by Bernard Koloski. New York: Penguin, 2002.

At Fault: A Scholarly Edition with Background Readings. Edited by Suzanne Disheroon Greeen and David J. Caudle. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2001.

Kate Chopin: Complete Novels and Stories. Edited by Sandra Gilbert. New York: Library of America, 2002.

Articles and book chapters about At Fault

Some of the articles listed here may be available on line through university or public libraries.

Fox, Heather A. Arranging Stories: Framing Social Commentary in Short Story Collections by Southern Women Writers. University Press of Mississippi, 2022.

Ostman, Heather. The New View from Cane River: Critical Essays on Kate Chopin’s At Fault. Louisiana State University Press, 2022.

Williams, Deborah Lindsay. “Absent Babies and Cosmopolitan Bananas: Fault Lines, Networks, and Modernity in At Fault”: 13-31.

Aikens, Natalie. “Reconciling the (Post)Plantation in At Fault: Reunion Romance, Western Expansionism, and the (Neo)Liberal Turn”: 32-63.

Knight, Nadine M. “At Fault and Antebellum Nostalgia”: 64-83.

Toth, Emily. “So Melicent Is a Unitarian: Who’s at Fault?”: 84-96.

Koloski, Bernard. “What Hosmer Wants: Male Aspirations in At Fault”: 97-114.

Bibler, Michael P. “Kate Chopin’s Queer Etiologies: What’s at Fault in the History of Sexuality”: 115-134.

Staunton, John A. “Quick, Dead, and Widowed: Failed Reading of ‘Unwholesome Intellectual Sweets’ and the Importance of Knowing Whose Story You’re In”: 135-155.

Ostman, Heather. “Divorce and the New Woman: Precedents to Modernism in At Fault”: 156-174.

Moldow, Susan. “Personified Matter: Empowered Things in At Fault.” 175-195.

Gil, Eulalia Piñero. “‘Thérèse Was Love’s Prophet’: The Emotional Discourse and the Depiction of Feelings in At Fault”: 196-214.

Smith Hart, Monica. “Arson And Murder In Kate Chopin’s At Fault.” Explicator 70.3 (2012): 179-182.

Campbell, Donna. “At Fault: A Reappraisal of Kate Chopin’s Other Novel.” The Cambridge Companion to Kate Chopin. 27-43. Cambridge, England: Cambridge UP, 2008.

Russell, David. “A Vision of Reunion: Kate Chopin’s At Fault.” Southern Quarterly: A Journal of the Arts in the South 46.1 (Fall 2008): 8-25.

Despain, Max and Thomas Bonner, Jr. “Shoulder to Wings: The Provenance of Winged Imagery from Kate Chopin’s Juvenilia Through The Awakening.” Xavier Review 25.2 (2005): 49-64.

Koloski, Bernard. “Introduction” At Fault New York: Penguin, 2002.

Anderson, Maureen. “Unraveling the Southern Pastoral Tradition: A New Look at Kate Chopin’s At Fault.” Southern Literary Journal 34 (2001): 1-13.

Witherow, Jean. “Kate Chopin’s Dialogic Engagement with W. D. Howells: ‘What Cannot Love Do?’.” Southern Studies 13 (2006): 101-116.

Menke, Pamela Glenn. “The Catalyst of Color and Women’s Regional Writing: At Fault, Pembroke, and The Awakening.” Southern Quarterly 37 (1999): 9-20.

Green, Suzanne Disheroon, and David J. Caudle. At Fault: A Scholarly Edition with Background Readings Knoxville: U of Tennessee P, 2001.

Fluck, Winfried. “Kate Chopin’s At Fault: The Usefulness of Louisiana French for the Imagination.” Creoles and Cajuns: French Louisiana–La Louisiane française. 247-266. Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang, 1998.

Cole, Karen. “A Message from the Pine Woods of Central Louisiana: The Garden in Northrup, Chopin, and Dormon.” Louisiana Literature 14 (1997): 64-74.

Warren, Robin O. “The Physical and Cultural Geography of Kate Chopin’s Cane River Fiction.” Southern Studies 7 (1996): 91-110.

Wagner-Martin, Linda. “Kate Chopin’s Fascination with Young Men.” Critical Essays on Kate Chopin. 197-206. New York: Hall, 1996

Tapley, Philip. “Kate Chopin’s Sawmill: Technology and Change in At Fault” in the Proceedings of the Red River Symposium, Red River Regional Studies Center in Shreveport, Louisiana, 1986.

Selected books that discuss At Fault

The New View from Cane River: Critical Essays on Kate Chopin’s At Fault, edited by Heather Ostman. Louisiana State UP, 2022.

Ostman, Heather. Kate Chopin and Catholicism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

Koloski, Bernard, ed. Awakenings: The Story of the Kate Chopin Revival Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009.

Beer, Janet. The Cambridge Companion to Kate Chopin Cambridge, England: Cambridge UP, 2008.

Ostman, Heather. Kate Chopin in the Twenty-First Century: New Critical Essays Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars, 2008.

Koloski, Bernard. “Introduction” At Fault by Kate Chopin New York, NY: Penguin, 2002.

Green, Suzanne Disheroon, and David J. Caudle. At Fault: A Scholarly Edition with Background Readings Knoxville: U of Tennessee P, 2001.

Walker, Nancy A. Kate Chopin: A Literary Life Basingstoke, England: Palgrave, 2001.

Toth, Emily. Unveiling Kate Chopin Jackson, MS: UP of Mississippi, 1999.

Petry, Alice Hall (ed.), Critical Essays on Kate Chopin New York: G. K. Hall, 1996.

Elfenbein, Anna Shannon. Women on the Color Line: Evolving Stereotypes and the Writings of George Washington Cable, Grace King, Kate Chopin Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 1994.

Boren, Lynda S. and Sara deSaussure Davis (eds.), Kate Chopin Reconsidered: Beyond the Bayou Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1992.

Perspectives on KateChopin: Proceedings from the Kate Chopin International Conference, April 6, 7, 8, 1989 Natchitoches, LA: Northwestern State UP, 1992.

Papke, Mary E. Verging on the Abyss: The Social Fiction of Kate Chopin and Edith Wharton New York: Greenwood, 1990.

Toth, Emily. Kate Chopin. New York: Morrow, 1990.

Elfenbein , Anna Shannon. Women on the Color Line: Evolving Stereotypes and the Writings of George Washington Cable, Grace King, Kate Chopin Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 1989.

Taylor, Helen. Gender, Race, and Region in the Writings of Grace King, Ruth McEnery Stuart, and Kate Chopin Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1989.

Bonner, Thomas Jr., The Kate Chopin Companion New York: Greenwood, 1988.

Bloom, Harold (ed.), Kate Chopin New York: Chelsea, 1987.

Ewell, Barbara C. Kate Chopin New York: Ungar, 1986.

Skaggs, Peggy. Kate Chopin Boston, MA: Twayne, 1985.

Leary, Lewis. “Introduction” Kate Chopin: The Awakening and Other Stories. New York, Holt, 1970.

Seyersted, Per. Kate Chopin: A Critical Biography Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1969.

Rankin, Daniel, Kate Chopin and Her Creole Stories Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1932.